Feminine Space in Jesse Jone’s No More Fun and Games

“In truth, there is nothing [women] can call their own but death, not even that small model of their servile clay which forms a paste and a cover to their bones”

– Anna Doyle Wheeler

Jesse Jones latest work No More Fun and Games is currently being exhibited at the Hugh Lane Gallery until 26th June 2016. It features themes of female empowerment and social renewal, lending itself to numerous interpretations of the feminine space. As an Irish based artist her work comes before Dublin’s public eye at a significant time, coinciding with the 1916 commemoration. Jones work is noteworthy at a time when women are being rightly reremembered as part of Ireland’s greater cultural memory.

The exhibition births with a pungent pink bloom, erupting in the opening passage adjacent to white winding hallway. On entering you are met with the curious music of Gerald Busby, his score Pneuma had been commissioned by Jones specifically for the exhibition. His work had previously featured in Robert Altman’s film 3 Women (1977) which heavily influenced the curation. The next sound is that of the great wave/spectre/shadow, as the wispy curtain is announced like rain patter. The arrival is as immediate as its subsequent slinking away. The great seam of it winds you along, commanding with the charm of a great serpent. Eerie would be the easy word.

As curator Michael Dempsey stated the exhibition seeks to raise feminist consciousness, mingling notions of consumption and production. One of the most immersive aspects is the incorporation of the cinematic features, introducing dramatic facets instead of focusing on aesthetics alone. The long extension of the forearm adopts the likeness of a snake as it slithers through the rooms. The hand itself is ghostly, beckoning with perfectly polished talons. The hesitant outreach winds seductively around the speakers dotted throughout until it comes to rest with a shudder. The pattern appears cyclical, raising questions regarding space allotted for feminine presence with its movements. One cannot but question the drive, is the presence repressed or territorial. Resigned to a slim-lined path throughout the gaping gallery space, the patriarchal expectation of female space is here easily suggested.

The chrome room, Gallery 14 that had been ordered by the Curatorial Collective of the Feminist Parasite Institution beholds seven pieces by ranging female artists. These pieces are related to Jones’ assertion of female representation within artistic institutions, opposed to the space previously taken up with the patriarchy. Condensed in one corner of the room are two works of unmistakable manifestation, Study of a Young Girl (1918-1922) by Gwen John and The Girl in White (1910-1912) by Grace Henry. These haunting depictions of women with steadfast eyes form an interesting commentary on female presence and the empowered artist. Gwen John is just one early instance of an artist who favoured her work at the refutation of the domestic. She once encapsulated her opinion simply in a letter to a friend “I think to do beautiful pictures we ought to be free from family conventions and ties.”

Further along the wall is Lodge (2016) by Elizabeth Magill. At a glance this work depicts a ghostly white house eclipsed by a darkened forest. If considered alongside musings of gendered space, the old home is reminiscent of restrictive domestic space. In the past the home was often considered to be an extension of the feminine, further representative of well rooted gender imbalance.

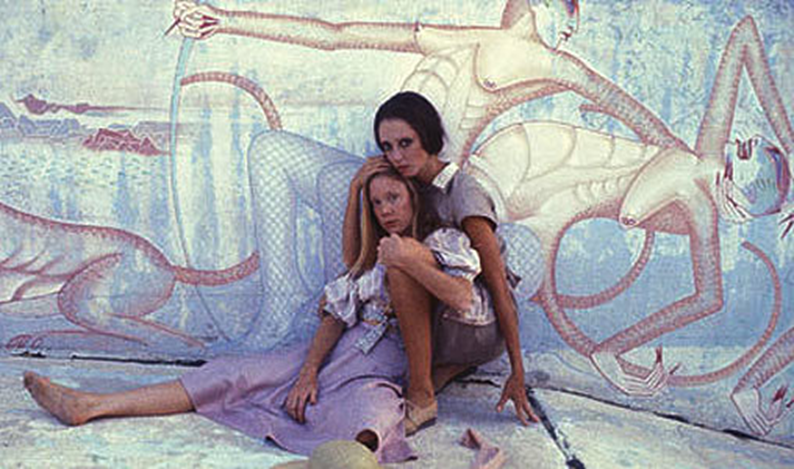

The music reveals an increasingly melancholy edge the longer you spend in the rooms. In 3 Women, just as the exhibition, the score appeared lulling in the opening. However this is sharply contrasted with the stark bodily imagery throughout the feature, familiarly pungent in colour. Just as the looped curtain moves throughout the gallery space, the progression of the film is cyclical itself. Altman’s influential film features fluidity and synchronization as a recurring motif. Due to the empowerment and unison of the feminine portrayed it is clear to see why the feature had influenced Jones’ curation.

Words: Jessica McKinney